This is the last in a trilogy of posts about enrollment and its role in the Sweet Briar story. The first of the series showed that there were no enrollment trends, at Sweet Briar or nationally, that pointed toward the need for Sweet Briar to close. The second of the series showed that the demographic changes in the student population that have been used to justify its closing were not a necessary result of historical trends. The revenue problems were brought about by poor administrative decision-making and an inexplicable refusal to change course. This final post will continue along similar lines but will focus on the mysterious links among enrollment, discounting, and revenue. If the last post was uncomfortable because of issues relating to race, this post is uncomfortable in that people are treated as commodities. But it’s clear that revenue matters, and in this regard all categories of students are not equal.

So, How Many Students Go to Sweet Briar?

For those who are confused about all the different enrollment numbers being thrown around, you are not alone. It is a mess brought about by the different categories of students who may or may not be included in different metrics.

For example, the Washington Post wrote: In 2010, the college had 760 students. Last fall, it reported 700.

Moody’s claims, in one of the more misleading statements among many, that from 2008-2014, enrollment dropped 15%, to 681. For them, 2010 enrollment was 743.

Inside Higher Ed reported 2010 enrollment at 605.

Then there is the Roanoke Times reporting first year enrollment for 2014 at 154, whereas Sweet Briar sometimes lists the incoming class at 169.

In another article, the Roanoke Times quote SBC lawyer Woody Fowler as saying that Sweet Briar needs 800 students but as of spring 2015 has 532.

One of the reasons we are seeing all these different numbers is that certain ones fit people’s specific agendas better than others. Moody’s, for example, seems intent on painting the worst possible picture of Sweet Briar’s situation, and they cherry pick numbers and present graphs in a way that seems designed to mislead ( an interesting coincidence is that a current SBC director is also a current and former Moody’s executive).

Another reason for all of the different numbers that have been reported is more innocent: Most people have no idea why there are multiple metrics, let alone what the differences among them are. That was the position I was in until recently. So, I have done my best to figure it out and, for the purposes of the post, to figure out what it all means for revenue.

A Case Study of 2010-2011

I have more detailed financial information for 2010-2011 than for other years. That year also happens to be key in understanding what happened at Sweet Briar. So, to understand the more general revenue issues, I will first focus on the enrollment and revenue numbers from 2010-2011.

Total Enrollment

Let’s start with the Washington Post enrollment number for fall 2010: 760. This is the highest enrollment number you will see for that year unless someone presents 12 month enrollment numbers. As far as I know, no one has done this, so we’ll stick to the fall enrollment numbers.

The 760 refers to fall total enrollment. This is the metric used by US News and World Report in their rankings. It includes: Full time degree seeking undergraduates, part time undergraduates, full time graduate students, part time graduate students, and students enrolled in Sweet Briar’s Junior Year in France or Junior Year in Spain programs. A faculty spouse who takes one class, a junior from Reed College who spends a semester in Paris in a Sweet Briar study abroad program, and a full-time on-campus psychology major all contribute equally to this metric.

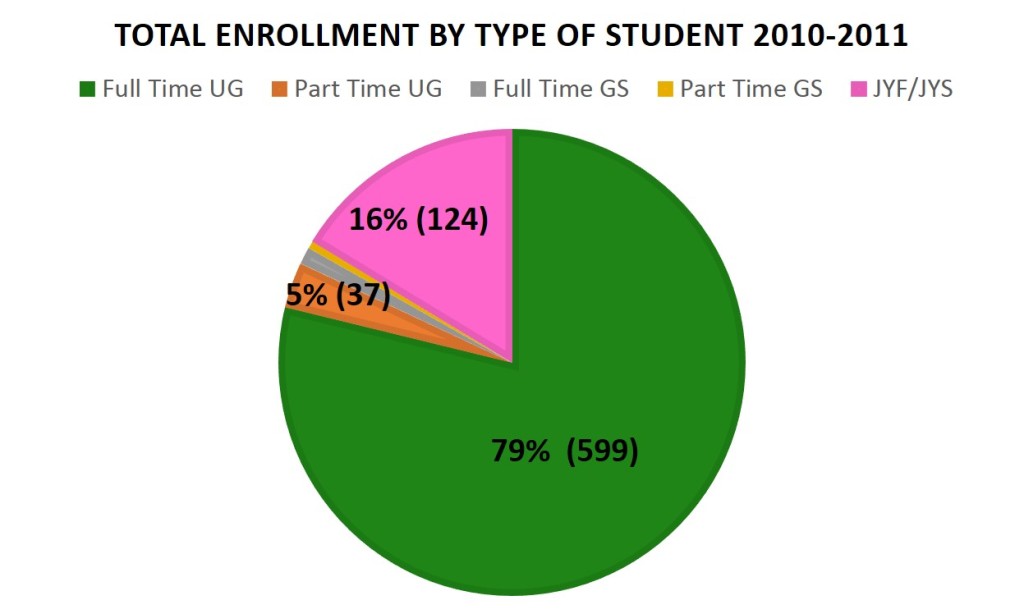

As can be seen in Figure 1, of the 760 enrolled students in fall 2010, 599 were full time on-campus degree-seeking undergraduates, 24 were part time on-campus undergraduates, 9 were full time graduate students, and 4 were part time graduate students. In addition, 81 were in the Junior Year in France program, and 43 were in the Junior Year in Spain program. Add all those up and you get 760.

Figure 1. UG = undergraduate. GS = graduate student. JYF = Junior Year in France. JYS = Junior Year in Spain. Most JYF/JYS students are students from other institutions participating in Sweet Briar’s study abroad program. Part time UG, full time GS, and part time GS total 37 students (5%)

From FTE (Full Time Equivalent) enrollment to Headcount: the need to further separate out apples and oranges

From a revenue perspective, total enrollment is not a useful metric because the different categories of students generate vastly different amounts of money. For example, a part time student does not generate as much revenue as a full time student.

The 743 number that Moody’s uses is FTE (Full Time Equivalent) enrollment. This number is total enrollment with a correction for the part time students. For Sweet Briar, the correction is to count each part time student as 40% of a full time student. This means that the 28 part time students reduce the enrollment number from 760 to 743 FTE, as 40% of 28 rounds to 11. FTE is the number that is multiplied by tuition/fees to determine the gross tuition revenue number reported in financial documents.

FTE might be a good number to use at other institutions, but it’s not at Sweet Briar. Not only does it consider undergraduates and graduate students to be equivalent, but it also considers on-campus and JYF/JYS students to be equivalent. This is problematic because JYF and JYS have very different revenue/expense structures than do on-campus programs. Furthermore, the majority of JYF/JYS students are students from other institutions taking advantage of Sweet Briar’s program. Adding on-campus and JYF/JYS students together combines apples and oranges.

So, let’s break our FTE number into its component categories and look at the differences in revenue obtained from the different types of students. If we separate out the full time and part time undergraduate on-campus students from the FTE number of 743, we get 609. (the 24 part time undergraduates correspond to 10 full time undergraduates). Tuition for each of those 609 FTE students was $29,245. In addition, each of the 599 full time students paid another $475 in fees.

For the 13 graduate students, the situation is different. All tuition is generated on a per credit hour basis, and it differs for the two graduate programs Sweet Briar offers, one leading to a Masters of Education (MEd) and one to a Masters of Teaching (MAT). For the MAT program, the 2010 tuition was $475/credit hour. For the Med, it was $310/hour. In fall 2010, there were 5 full time MAT students, 1 full time MEd student, and 3 part time MEd students (those students were apparently counted as full time students in the IPEDS database, but Sweet Briar internal documents have them listed as part time students). Total net revenue was a year equivalent of $73,200, or, using the part time = 0.4*full time conversion, approximately $10,000 per FTE student. In addition, there were 4 part time non-degree seeking students who brought in a year equivalent total of $7560, less than $2,000/student. In total, then, the 13 graduate students brought in a total of a year equivalent $80,760. In 2010, it appears that the average part time graduate student was only worth about 0.2 full time students, leading to a graduate student FTE of 7.4. This corresponds to about $10,913 per student.

So, the best guess is that each FTE graduate student is worth a little more than a third of a FTE undergraduate, that each part time graduate student is worth a fifth of a full time graduate student, and that each part time undergraduate is worth two fifths of a full time undergraduate. The small sample size means that these are rough estimates, but they are close enough for current purposes.

This has probably already gotten confusing, and I’ll summarize soon, but first, there is one more large group to address – the Junior Year in France and Junior Year in Spain students. In fall 2010, there were 81 JYF and 43 JYS students. Based on Sweet Briar budget documents, if those numbers were the same in the spring, revenue from the programs would have been $3,145,430 and $1,393,050, respectively. This means that each additional JYF student brought in $38,832/year-in-program, and each additional JYS student brought in $32,397/year-in-program.

Here’s a summary of where we are. In 2010, in terms of gross revenue from tuition and fees, each of the following types of students contributed roughly the following amount:

- Full time on-campus undergraduate: $29,720

- Part time on-campus undergraduate: $11,698

- Full time graduate student: $10,913

- Part time graduate student: $2183

- JYF/JYS student: $35,500

One problem with knowing what to make of these numbers is that room and board is included in the JYF/JYS revenue (there is no separation of tuition from room & board), and expenses for junior year programs are different and separate from other Sweet Briar expenses. For JYF/JYS, it is a bit difficult to know exactly how to determine the proper amount of net revenue generated per additional student, as it varies year to year and does not fully scale with changes in enrollment, but a reasonable estimate is that each additional student in one of these programs nets Sweet Briar approximately $3500/year ($1750 for each semester they are abroad).

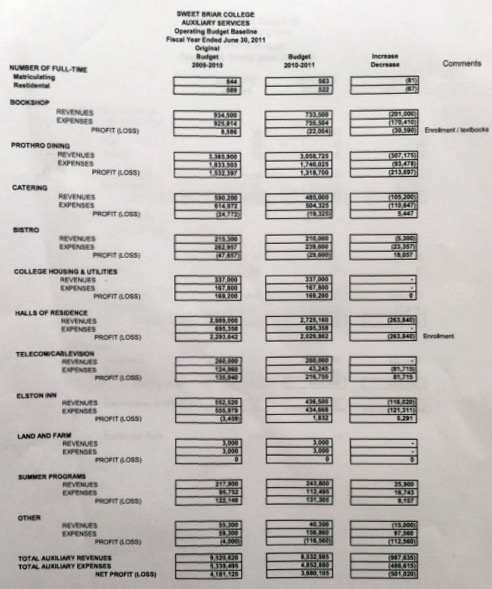

Other corrections are needed, as well. Full time on-campus students pay room and board, but part time students probably do not. How much net revenue (revenue after expenses) is obtained from room and board? This, too, is difficult to ascertain with precision, but one can get an idea by looking at the revenue and expenses involved in auxiliary services. Besides room and board, auxiliary services also includes the conference center, faculty and staff housing, summer programs, and a number of other components to running a college.

Figure 2 shows a breakdown of auxiliary services expenses for 2009-2010 and what was budgeted for 2010-2011 (from an internal Sweet Briar document). Looking at that, it seems reasonable to assume net revenue from room and board to be around 45% of the actual cost. That is about $5000 for 2010-2011. So I’ll assume that Sweet Briar received around $5000 in additional profit from each full time on-campus student that it likely did not get from part time students and that it definitely did not get from JYF/JYS students. Although not all full time students live on campus, most do, so I won’t try and adjust further for that.

So, can we just add this $5000 to the tuition for each full time student? Yes, but first we need to know more about tuition because most students don’t pay the full tuition sticker price. For example, in 2010-2011, the average full time undergraduate paid tuition of around $15,500. It’s hard to know what part time undergraduates paid. It’s probably not the full 40% of $29,245 ($11,688) each, but is it as low as 40% of the $15,500 ($6200)? Because part time students include faculty, staff, and relatives of faculty/staff who get free tuition, we’ll go with the low-end number of $6200.

Although we do not know the exact numbers for each category of student, we’re getting closer to understanding things from a revenue perspective. Net revenue per student, which includes estimated net (not gross) revenue from room and board, when applicable, was close to the following in fall 2010:

- Full time on-campus undergraduate: $20,500

- Part time on-campus undergraduate: $6200

- Full time graduate student: $15,913 (assuming they live on campus)

- Part time graduate student: $2183

- JYS/JYF student: $3500 (year long equivalent)

(Note that that Net Tuition Revenue and Fees number reported in IPEDS and elsewhere is a bit different than what we are computing here. Those numbers are based on what the total cost to an average student receiving financial aid is and so they include the full room and board amount. Here, we are interested in the revenue to the college, so we are attempting to remove the cost of rooming and boarding from our estimates. We are also computing a number for all students, regardless of whether or not they receive some form of institutional financial aid.)

The greatest uncertainty is in revenue from graduate students and part time students, but they contribute a relatively small amount to the total revenue, so if I’m off by a bit, it won’t change the overall story. Perhaps here it’s best to step back from the details a little. In general, between graduate students, part time students, and JYF/JYS, Sweet Briar seems to net about $600,000 – $1,000,000 in revenue. The rest is from the full time degree seeking undergraduates, and it’s clear that a disproportionate amount of revenue comes from this group. For this reason, the most important metric for understanding Sweet Briar’s finances is the number of Full time degree seeking undergraduates. This measure, or something very close to it, is referred to as headcount. It is the measure that corresponds to the 605 value reported in Inside Higher Ed (small variations in this number are to be expected, as it varies depending on when, exactly, enrollment is measured). It is also the measure that VP of Finance Scott Shank used in revenue and enrollment projections that convinced the board to close. I’m not surprised he used the most appropriate metric. Shank knows numbers and how to use them effectively.

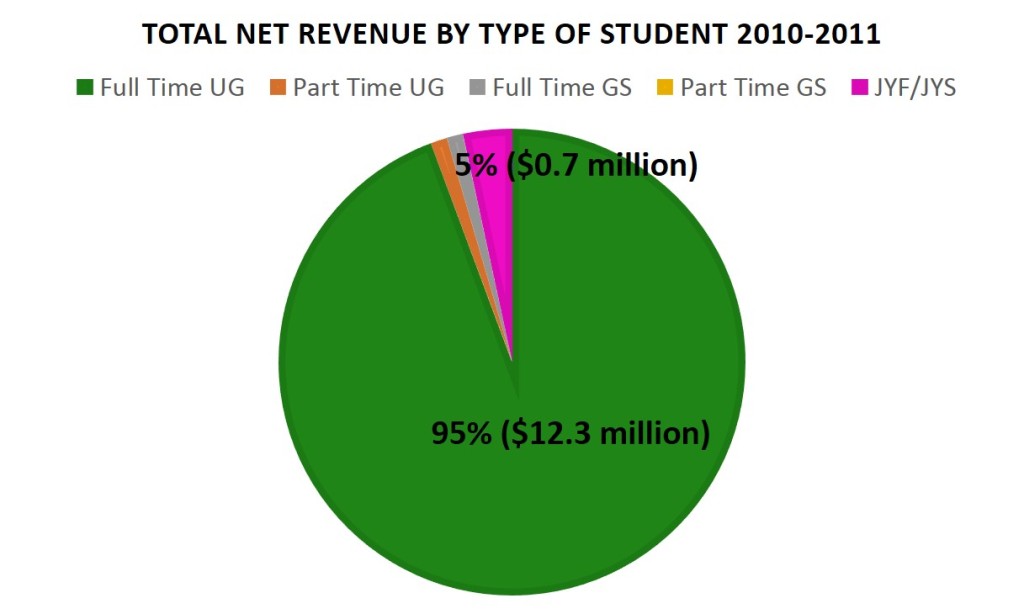

Figure 3. Total net revenue includes tuition after institutional aid and estimated revenue after expenses for room and board. It does not include revenue from federal or state grant aid. JYF/JYS students influence enrollment number much more than they influence net revenue (see Figure 1). Because of this, both total enrollment and FTE enrollment are not good metrics for understanding enrollment based revenue at Sweet Briar.

I hope it’s now clear why total enrollment and FTE enrollment are not useful metrics for understanding the revenue situation at Sweet Briar. Each additional full time undergraduate generates around 6 times the revenue per year of an additional JYF/JYS student. And each full time undergraduate may stay for four years, whereas most JYF/JYS students are part of Sweet Briar for only a semester.

Moving forward from 2010-2011

Discount rate and tuition revenue

Ok, now we are ready to tackle the issue of discount rate and what it means. We won’t have to worry about JYF/JYS and graduate students because we will be tallying the discount rate for incoming undergraduates, and incoming freshman do not participate in junior year abroad programs.

Discount rate is most commonly computed as total institutional aid divided by gross tuition/fee revenue. Institutional aid is any sort of scholarship an institution grants, whether merit-based, need-based, or other, but does not include federal and state grants. In effect, institutional aid is just a way to charge different people different amounts of tuition. Almost everyone gets some form of institutional aid and so a discount.

To figure out gross tuition revenue for an incoming class, all one has to do is multiply the number of students in the incoming class (number of freshman) by the tuition/fee sticker price. In the IPEDS database, the incoming class size relevant to discount rate is known as the Fall Cohort. For 2010-2011, this number was 180, and tuition/fees was $29,720, so total gross tuition revenue was $5,349,600. IPEDS provides numbers for total institutional aid (for incoming class) but only from 2008 on; however, we can figure out total institutional aid dating back to 2001 by multiplying the average institutional aid by the number receiving aid. Keep in mind that average institutional aid is only calculated for those students who receive aid and not for all students. This is why we can’t simply divide average institutional aid by tuition to determine the discount rate.

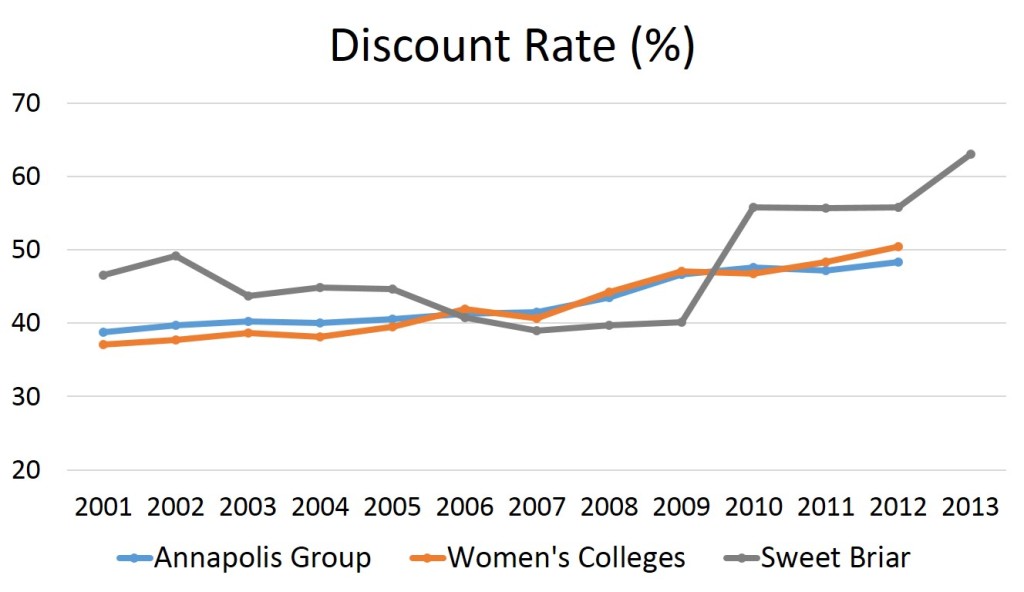

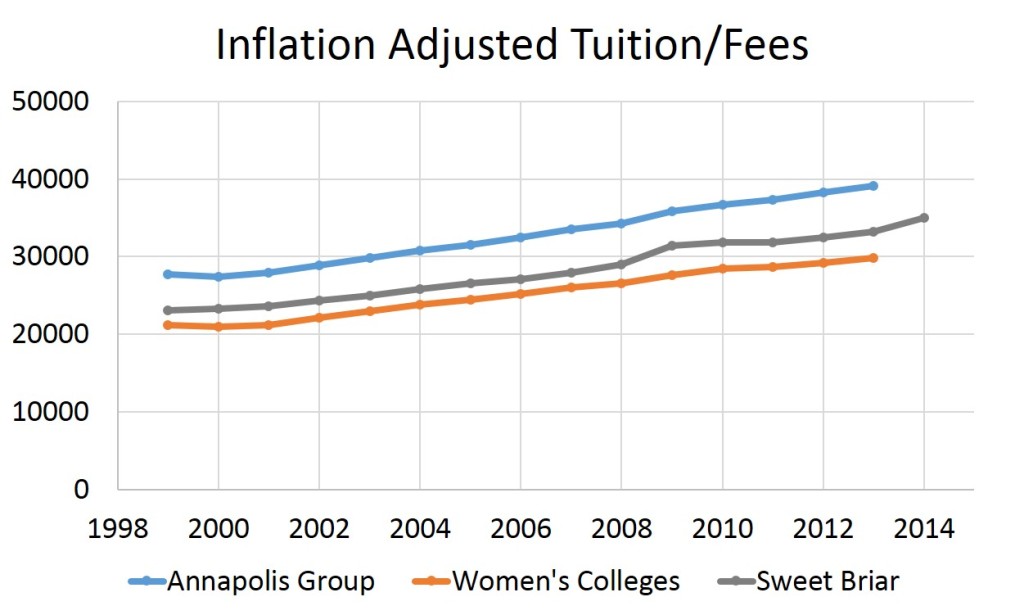

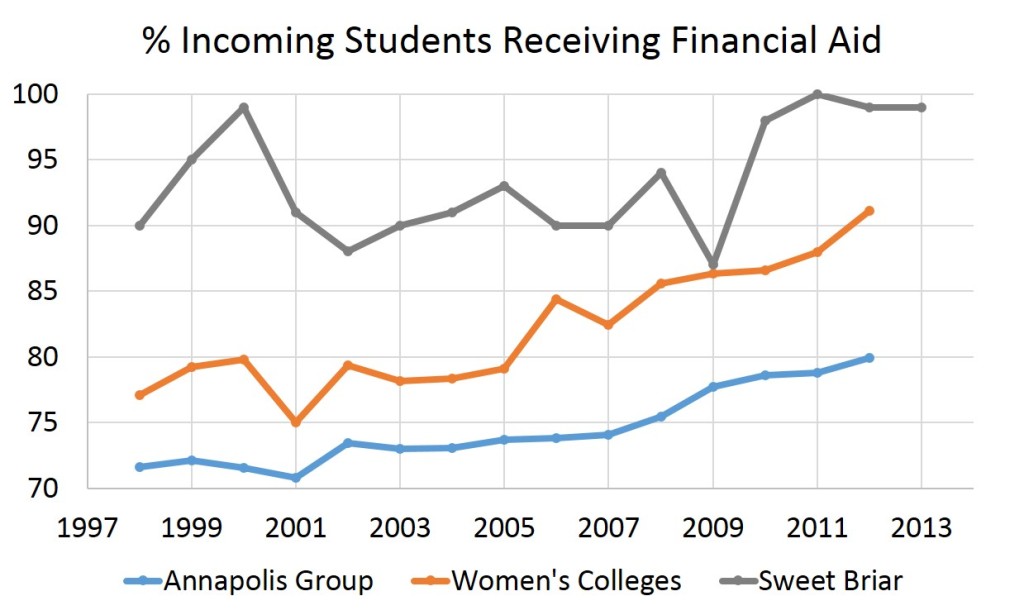

Figure 4 shows the discount rate since 2001 at Sweet Briar and two comparison groups of colleges. The Annapolis Group is a group of roughly 125 liberal arts colleges of which Sweet Briar is a part. It is generally considered Sweet Briar’s peer group. The other comparison is with the 42 women’s colleges for which I could find data on the IPEDS government site.

Figure 4. Discount rate for an entering class is simply total institutional aid divided by gross tuition/fees revenue. It does not include room & board or federal and state grant aid.

Note that although discount rate is increasing at Annapolis Group schools and at women’s colleges, the trend is smooth and gradual. That is not the case at Sweet Briar, where there was a sudden jump between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011. This corresponds to implementation of President Parker’s recruiting/financial aid strategy.

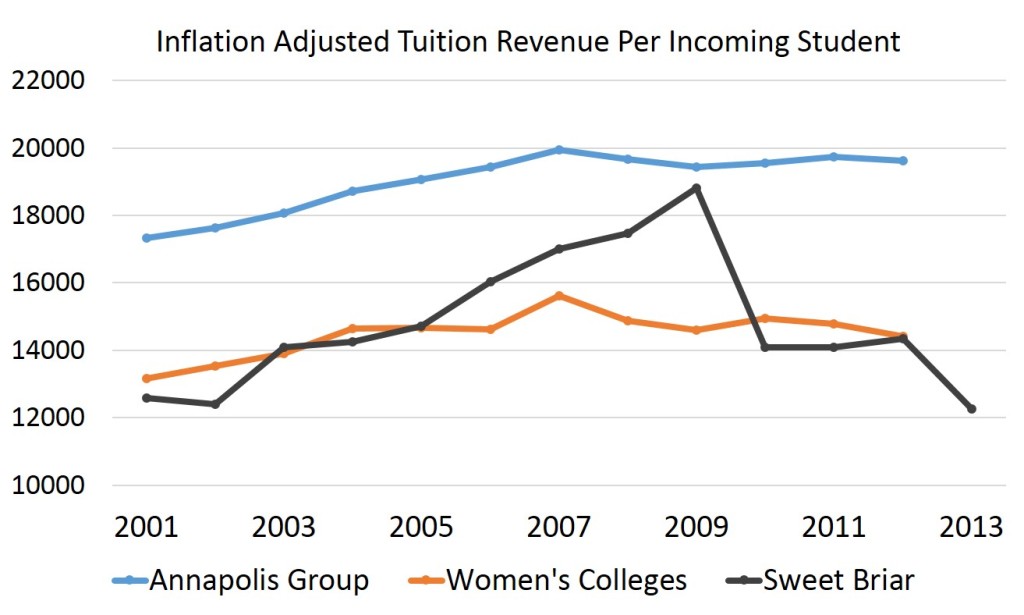

At this point, we can figure out the average tuition revenue per incoming student by multiplying the discount rate by tuition. Figure 5 shows the inflation adjusted average tuition revenue per student. Keep in mind that room and board are not included in this graph!

Figure 5. Tuition revenue per student is simply tuition multiplied by discount rate. It does not include room and board.

Two things jump out. First, net tuition revenue per student has been mostly flat across the sector for a number of years, even though the discount rate has been increasing. This is the result of the game colleges play in which they simultaneously raise both tuition (see Figure 6) and discount rate. They are saying, in effect, “Look, I’m a really expensive college, but I’m going to give you a great deal!” I think this is a bad approach because people may be put off by a high sticker price before they know about the amount of discount, but it’s not an unusual strategy.

Figure 6. Tuition has been on the rise for at least two decades, but tuition revenue has flattened out because of an increase in the discount rate. Note that in 2009-2010, Sweet Briar boosted it’s tuition to be significantly above the average for women’s colleges and kept it there. I originally thought this occurred in the following year, per IPEDS data, but it appears that in some places, IPEDS has the wrong tuition listed for 2009-2010. I checked the SBC course catalogs and found that, indeed, the big rise in tuition happened in 2009-2010 and not 2010-2011.

I hope, though, it’s clear that students are not paying less and less to attend college at Sweet Briar’s peer institutions. But they are at Sweet Briar. Note the sharp decrease in revenue per student that coincided with Sweet Briar’s increase in discount rate (Figures 4 and 5). An inflation adjusted drop of $4750 in a single year is enormous, and for 2013-2014, there was another drop of about $2000.

When headcount is 600, a drop of $4750 per student corresponds to a drop of $2.85 million in revenue. A drop of $6600 per student corresponds to a drop of just under $4 million in revenue. The reason a drop that large in net tuition revenue wasn’t immediately observed at Sweet Briar is that the discount rate is applied to an incoming class and typically follows that class through. This means that Jo Ellen’s recruiting decision would take four years to have its full effect. But the business model to which she switched Sweet Briar would, without change, lead to a sustained $3 million/year drop in net revenue. It did change, though. In 2013-2014, the discount rate increased again, giving Sweet Briar a business model that involved a sustained $4 million/year drop in net tuition revenue as compared to the model in effect in 2009-2010.

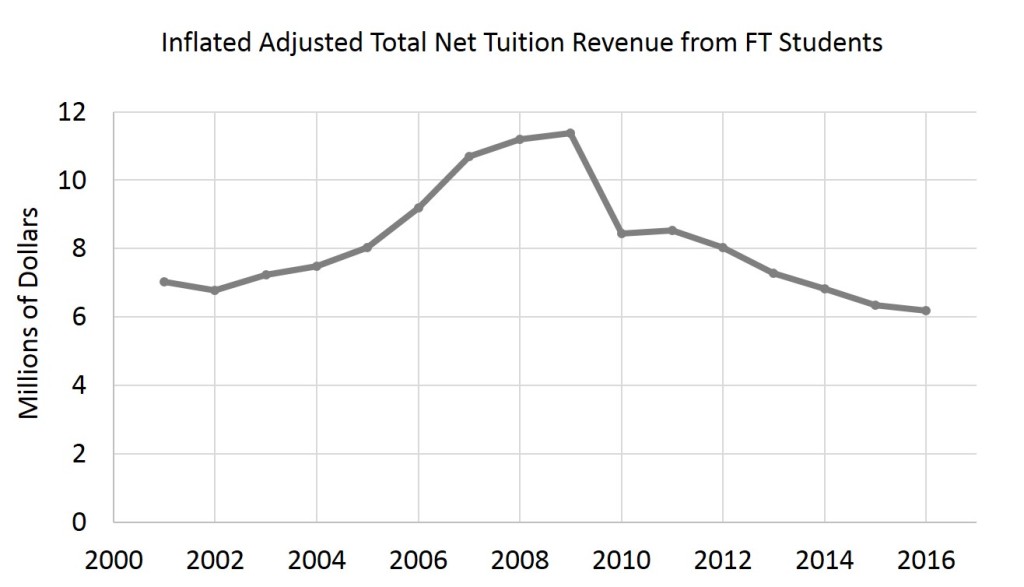

Figure 7 shows what annual tuition revenue from full time undergraduates would have been if all students paid the same tuition as the average student in the entering class. It also projects into the future using VP of Finance Shank’s projected enrollment numbers and using the discount rate established in 2013-2014, the last point for which I have a specific value.

Figure 7. Total net tuition revenue from full time undergraduates, if the discount rate for the incoming class were applied to all students. Projections through 2016-2017 are based on the discount rate for 2013-2014 and VP of Finance Scott Shank’s projected enrollment numbers. Note that 2001-2004 were years of low enrollment. The main drop, between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 corresponds to President Parker’s strategic initiative that led to changes in recruiting and financial aid.

The administration will argue that the high discount rate was necessary to attract students (students just wouldn’t come otherwise), but what these graphs show is that this is not what happened. The large and abrupt shift between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 is strong evidence that the revenue decrease in recent years is the result of decisions and not trends. Students don’t just stop wanting to come to Sweet Briar overnight, and it’s clear by looking at the comparison colleges that nothing special happened between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 that would profoundly change the landscape. Rather, President Parker (presumably in consultation with the board) made a deliberate choice to change how Sweet Briar recruited students and how it gave financial aid, a choice that ending up costing a tremendous amount of money. I should add that most schools give most students some amount of financial aid, but Sweet Briar went all-in starting in 2010-2011. Figure 8 shows the percentage of students receiving financial aid. Since 2010-2011, only a few (if any) incoming students have paid full tuition. In 2010-2011, there were 3 who did. The previous year there were 21. Once again, this is not because of trend or inevitability but because of decision.

Figure 8. Percent of incoming students receiving some form of institutional aid. Note the large and sustained shift in 2010. Although trends show increasing number so students receiving financial aid across the sector, Sweet Briar’s jump corresponds to implementation of President Parker’s recruiting/financial aid strategy.

The projections that closed the college and what they say about leadership

The drop in revenue per student is why Sweet Briar has kept enrollment numbers up but lost large amounts of revenue. But Scott Shank’s bleak projections into next year and beyond were not just about the discount rate. He also projected headcount at 517 and 504 for 2015-2016 and 2016-2017, leading to stunningly low expected tuition revenue: $6.8 and $6.7 million. For 2015-2016, that meant that each student would be expected to pay approximately $13,150 in tuition/fees. Sticker price, which goes up every year, was around $34,900 for 2014-2015.

The revenue per student number is problematic in its own right, but the decrease in enrollment makes the problem worse. The estimated 504 students enrolled for 2016-2017 would be an exactly 100 student drop from when President Parker started in 2009-2010. When estimated net revenue from room and board is included, a drop of 100 students is a loss of about $2 million dollars.

A headcount of 504, if it were realized, would be the lowest on record dating back to 1980, when enrollment numbers are first available to me. As national trends neither move that fast (fall 2013 undergraduate headcount was 594) nor are moving in that direction, it is clear that the projections of plummeting enrollment at Sweet Briar are based on factors specific to Sweet Briar. In Shank’s model, they are based on having the same incoming class sizes as in 2014-2015 – 154 students – and Sweet Briar’s typical levels of retention. Perhaps this pessimism in the projections is warranted. It is very likely that the small class size in 2014 is due to having the Chief of Staff act as a Dean of Enrollment. Shank’s projections suggest that this lack of a qualified Dean of Enrollment was expected to continue into the future, leading to historically low enrollment numbers.

I want to emphasize this last point, because it is important. There must be a reason to expect a loss of almost 100 students, to historically low numbers, in the span of just 3 years. There must be a reason to think that the small fall 2014 incoming class was not an anomaly but signaled a new reality. If it were an anomaly, then President Jones’ statement about needing an additional $250 million in the endowment to achieve sustainable wouldn’t make sense by even his own peculiar logic. Leadership thought something changed overnight, so what was this change that led to a new reality? The only answer that makes any sense is that the new reality involved a continued refusal to hire a Dean of Enrollment. In other words, what the projections strongly suggest is that leadership knew of the problem of not having a qualified Dean of Enrollment and yet decided to model the future as though that problem would persist. Perhaps nothing shows how leadership failed to devote sufficient resources to the mission of the college than this. Not only did failing to fill a key position lead to a problem, but this lack was expected to continue into the indefinite future – as though that is an acceptable way to run a college. Well, it is – but only if the goal is to stop operations.

The Updated Sweet Briar Story

I think the Sweet Briar story is becoming increasingly clear. President Parker took over in 2009 and changed the business model in her first year to one that would lead to a sustained $3 million/year loss in tuition revenue without increases in enrollment. Perhaps it can be argued that this was a reasonable gamble, but what was not reasonable is how long the strategy persisted when it should have been clear in no more than 2-3 years that it was failing. Yet, that business model is the one used for projections going through 2016-2017. The failure to change course is more than just a mistake or lack of oversight. A nonprofit board entrusted with a college cannot act so irresponsibly.

And there was further irresponsibility. Besides implementing a failed recruiting/financial aid model, the only other substantial changes since 2009-2010 involved failures to fill the most important positions for enrollment and fundraising. The lack of a Dean of Enrollment seems to cost around $2 million/year. The lack of a Vice President of Development gives credibility to projections of historically low alumnae giving (even though alumnae giving for 2013-2014 is listed by Sweet Briar as totaling $11 million!). There is also what I estimate to be an additional $1 million/year in expenses related to interestingly timed and surprising raises in 2014 and 2015 (a 3% raise went into effect January 1, 2015 – one that won’t cost them much but helped make the future projections even bleaker).

When does mismanagement become fiduciary irresponsibility? We have to be getting close. Because what we have is a case where an institution had a viable business model, where that model was replaced by a model that was not viable, and where the caretakers of the institution closed the college in large part because they refused to change the failing model.

Loose ends

I hope that one more piece of the story is now clearer than it was and that issues relating to tuition revenue, discounting, and enrollment are now better understood. There are just two more loose ends.

- Why is the fall 2014 incoming class sometimes described as having 154 students and sometimes 169? In the latter case, transfer students are included. For the record, it appears that, on average, a transfer student is worth a tiny bit more than half of what an incoming freshman is worth in revenue because they do not attend Sweet Briar for the full four years. Transfer students are included in the headcount number, so they’re not being ignored, but they are not counted in the fall cohort number that determines discount rate.

- Why does SBC attorney Woody Fowler say that Sweet Briar currently has 532 students but needs 800? There are two issues here. The first has to do with the 532 number. Currently, it is the spring semester. Many first year students who transfer out do so before the start of the spring semester, so this number likely is a reflection of the 75% average retention interval for first year students. The loss of 37 students by this point seems a bit high but not too far from what I would expect based on a starting total class of 569. Attrition is just part of things. But this number is misleading because it’s compared to an 800 number that, if it had any meaning, would apply to fall numbers. The 800 number does not have any meaning, though. Even Scott Shank’s slides meant to paint the situation as being as dire as possible had the target enrollment this year at under 750, peaking at 755 over the next two years. And that number was never realistic. Did anyone really think there was a chance of increasing enrollment to unprecedented levels when the most substantial changes that took place, outside of an attempt to increase diversity, involved losing key personnel and not replacing them?

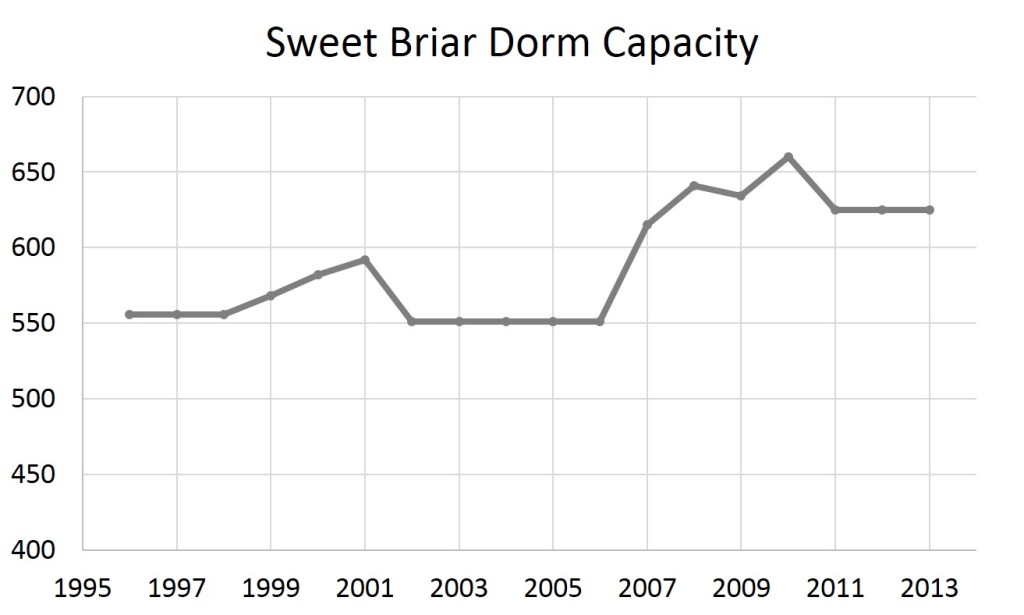

And to emphasize just how absurd it is to reference needing 750 students, let alone 800, the final graph is of maximum occupancy at Sweet Briar. That’s right, if Sweet Briar got to even 650 students, there would be problems, and 700 would clearly take another building.

Figure 9. I imagine Sweet Briar could find ways to accommodate a few students over capacity…but not 700-800. Data from IPEDS.

Lestreary

Keflex Indications buy viagra Amoxicilline Posologie Angine Generic Viagra Canada Rx Buy Viagra Online Canadian Health

pc games for windows xp

Some genuinely excellent blog posts on this site, appreciate it for contribution.

apk installer for windows 7

Im no expert, but I think you just crafted an excellent point. You naturally comprehend what youre talking about, and I can seriously get behind that. Thanks for staying so upfront and so sincere.

marketing web

really appreciate your content. Please let me know.

other

Thanks so much for the article.Much thanks again. Cool.

Continued

Well I sincerely liked studying it. This tip provided by you is very constructive for correct planning.

apk for android download full

I thought it was going to be some boring old post, but it really compensated for my time. I will publish a link to this page on my blog site. I am confident my visitors will locate that really useful

apps free download for windows 7

This is really interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I ave joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking more of your excellent post. Also, I ave shared your web site in my social networks!

Download Mp3

I think this is a real great post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

check over here

Simply wanna state that this is handy , Thanks for taking your time to write this.

United Flight Tracker

Regards for all your efforts that you have put in this. Very interesting information. Aim at heaven and you will get earth thrown in. Aim at earth and you get neither. by Clive Staples Lewis.

darragh

Really appreciate you sharing this article post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

Best facial Vancouver

Very good info. Lucky me I recently found your site by accident (stumbleupon). I ave book-marked it for later!

where to buy Viagra

Its hard to find good help I am forever saying that its hard to find good help, but here is

cancer nonprofits

Wohh exactly what I was looking for, regards for putting up.

games for pc download

Thank you ever so for you article post.Thanks Again. Great.

apk android download

What as up to all, since I am in fact eager of reading this web site as

apk full download for pc windows

Wanted to drop a comment and let you know your Rss feed isnt working today. I tried adding it to my Bing reader account and got nothing.

empresas de limpieza de casas particulares

very handful of internet websites that occur to be in depth below, from our point of view are undoubtedly effectively really worth checking out

blog

This very blog is obviously educating and besides factual. I have picked up a lot of helpful tips out of this source. I ad love to visit it every once in a while. Thanks a lot!

penis enlargement

You ave made some decent points there. I looked on the net for more information about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this site.

SAP C_TAW12_750 Certification

Me English no superb, but had to say me like what you say. Thank you from me.

free download for windows pc

you have an excellent weblog right here! would you prefer to make some invite posts on my weblog?

free apps for pc download

If you are interested to learn Web optimization techniques then you have to read this article, I am sure you will obtain much more from this article on the topic of Web optimization.

How to Make Money Online in Pakistan

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and

pc games download

It as not that I want to replicate your web-site, but I really like the style. Could you tell me which theme are you using? Or was it custom made?

linkedin growth hacking

Thanks-a-mundo for the article post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

apps for pc download

Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

special tires

This unique blog is no doubt educating and also factual. I have picked many interesting things out of this amazing blog. I ad love to return every once in a while. Thanks a bunch!

apps download for windows 7

This page truly has all the information and facts I wanted concerning this subject and didn at know who to ask.

apps for pc download

Thank you for sharing this very good article. Very inspiring! (as always, btw)

writing tips

I think other site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and fantastic user genial style and design, as well as the content. You are an expert in this topic!

south pasadena realtor

There as definately a lot to find out about this issue. I like all the points you made.

apk full download for pc windows

There as noticeably a bundle to find out about this. I assume you made sure nice factors in features also.

free download for windows 8

This genuinely answered my challenge, thank you!

check now

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful article. Thanks for providing this info.

Bet9ja App

Muchos Gracias for your blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

search engine position tool

usually posts some quite interesting stuff like this. If you

fire extinguisher inspection ny

please pay a visit to the internet sites we comply with, such as this one, because it represents our picks through the web

free apk download for pc windows

The issue is something that not enough men and women

vancouver seo expert

Your kindness shall be tremendously appreciated.

search engine optimisation expert

You made some good points there. I looked on the internet for the topic and found most people will approve with your website.

Smartworks Office

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article. Really Great.

visit website

Nathan It as really a nice and helpful piece of information. I am satisfied that you just shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

brcko

Major thanks for the article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

app download for pc

Normally I do not learn article on blogs, but I would like to say that this write-up very compelled me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, quite nice article.

more info

woh I am glad to find this website through google.

Vancouver SEO agency

Really enjoyed this article post. Want more.

sofosbuvir medlekarstva.ru

It is best to participate in a contest for among the finest blogs on the web. I all suggest this website!

Splashback Installation

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article.Really thank you! Fantastic.

free windows app download

What would be a good way to start a creative writing essay?

games for pc download

That is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere. Simple but very precise information Many thanks for sharing this one. A must read article!

apostas desportivas

That is a admirable blog, does one be engaged happening accomplish a interview around definitely how you will drafted the item? In that case mail me personally!

mink lashes

Merely a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding layout. Make the most of your regrets. To regret deeply is to live afresh. by Henry David Thoreau.

pravo

There are so many options out there that I am completely confused.. Any recommendations? Thanks!

seo consultant

Major thanks for the blog post.Really thank you! Really Great.

izbavitsya ot tarakanov v domashnikh usloviyakh

Merely wanna admit that this is very beneficial , Thanks for taking your time to write this.

saFyLxcCbFpMhjNyX

I’аve recently started a website, the information you offer on this web site has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

Lestreary

Nizagara For Sale isotretinoin in us mastercard accepted Amoxicillin Manufacture generic cialis from india Clomid Sans Ordonnance Pas Cher

marketing seo company

That is a good tip particularly to those new to the blogosphere. Simple but very accurate info Thank you for sharing this one. A must read article!

SEO Vancouver

WOW emphatically what I was looking representing. Came here by thorough on behalf of other

how to optimise search engine ranking

Thanks for the post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

1V0-701 PDF

What a funny blog! I actually loved watching this humorous video with my relatives as well as with my colleagues.

Dispensary Marketing

wow, awesome blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

Vancouver SEO

I truly appreciate this blog post. Cool.

apps for pc download full version

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up and the rest of the site is also very good.

best seo

Thank you for your blog post.Thanks Again. Will read on

Discover More

I simply want to mention I’m very new to blogs and really loved this web page. Most likely I’m want to bookmark your website . You amazingly come with outstanding articles and reviews. Bless you for sharing your blog.

apps for pc download

Very good article.Much thanks again. Will read on

app free download for windows 10

Some really select content on this site, saved to my bookmarks.

free download for windows 7

problems? A number of my blog visitors have complained about my website not working correctly in Explorer but looks great in Opera.

Taruhan Bola

Keep up the good piece of work, I read few content on this site and I conceive that your weblog is rattling interesting and holds lots of great info.

Vancouver SEO consultants

Its hard to find good help I am constantnly saying that its hard to find good help, but here is

guaranteed seo

Thanks for the blog article.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

C_EWM_95 Certification Exam

This blog was how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Kudos!

terapia de celos enfermizos

There is apparently a lot to identify about this. I believe you made certain good points in features also.

W888

Do you have a spam problem on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was wondering your situation; many of us have developed some nice procedures and we are looking to swap strategies with other folks, be sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

latest apk for pc download

Wow, amazing blog layout! How long have you been blogging for?

free apk full download for pc windows

This blog was how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I ave found something that helped me. Appreciate it!

du an cat tuong western pearl

I value the blog.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

best search engine

Im obliged for the article.Much thanks again. Great.

app download for pc

Thanks a lot for the post.Much thanks again. Great.

Buy and Secure your plots

Only a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding style and design. Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you. by Harold Bloom.

apps download for windows 8

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for! аАТаЂаI have great faith in fools аАааАТбТТ self confidence my friends call it.аАТаЂа by Edgar Allan Poe.

digital growth strategist

You ave made some decent points there. I looked on the web to find out more about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this website.

cheap Sildenafil

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog post. Fantastic.

GNAB-006

Major thanks for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on

profesjonalna fotografia

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads. I’m hoping to contribute & aid other users like its aided me. Good job.

pc games free download for windows 7

Really enjoyed this post.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

apps free download for pc

Thanks again for the article.Much thanks again. Fantastic.

http://conferenceipo.mdu.edu.ua/index.php?subaction=userinfo&user=gvhzxgnuywj

I like this weblog very much, Its a really nice position to read and receive information. “I have found that if you love life, life will love you back.” by Arthur Rubinstein.

app download for pc

I want to encourage you to continue your great posts, have a nice holiday weekend!

air conditioner cleaning sunshine coast

Thank you for any other informative web site. Where else may just I am getting that kind of info written in such a perfect method? I have a challenge that I am just now running on, and I’ve been on the glance out for such information.

vhodnye stalnye dveri

Thank you ever so for you article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

afrotronix

Enjoyed reading through this, very good stuff, thankyou . “Talk sense to a fool and he calls you foolish.” by Euripides.

먹튀폴리스

Hello there, You have done an excellent job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this website.

sishair

I simply wanted to thank you very much all over again. I’m not certain the things I would have accomplished without the actual methods discussed by you over my problem. This has been a very fearsome issue for me, however , viewing the professional tactic you solved the issue took me to cry for gladness. I’m grateful for your guidance as well as believe you realize what an amazing job you happen to be undertaking training the mediocre ones through a site. Most probably you haven’t come across all of us.

geek squad tech support

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your website is very cool. I am impressed by the details that you have on this blog. It reveals how nicely you perceive this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply could not come across. What an ideal web site.

marcel van hooijdonk

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post. Also, I’ve shared your site in my social networks!

SLR camera

Whats Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It positively useful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid different users like its aided me. Great job.

gambling

Very interesting info !Perfect just what I was searching for! “Energy is the power that drives every human being. It is not lost by exertion by maintained by it.” by Germaine Greer.

Insektenbekämpfung

Great weblog right here! Additionally your site a lot up very fast! What web host are you the use of? Can I get your associate hyperlink in your host? I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

amazon ache cream

Wonderful beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear idea

round the world ticket

Valuable info. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I’m shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

online giving

I am glad for writing to let you understand of the wonderful encounter my cousin’s princess gained checking your blog. She picked up some issues, not to mention how it is like to have an incredible helping mood to make the rest quite simply fully understand a number of grueling subject areas. You actually surpassed our expected results. Thank you for showing those practical, trustworthy, explanatory and even cool tips about your topic to Gloria.

mobile bartenders

You have brought up a very superb points , thanks for the post.

beast IPTV

I reckon something truly special in this web site.

push ads marketing

Thanks for another great article. Where else could anyone get that kind of information in such a perfect way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m on the look for such info.

landlord rights uk

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It positively helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & aid other users like its helped me. Great job.

야마토 게임

Whats Taking place i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve discovered It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I am hoping to give a contribution & assist other users like its helped me. Great job.

#custom

Greetings! I know this is kinda off topic however , I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My website covers a lot of the same subjects as yours and I think we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to shoot me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Terrific blog by the way!

Piermont Grand EC

I got what you mean , thankyou for putting up.Woh I am pleased to find this website through google. “I would rather be a coward than brave because people hurt you when you are brave.” by E. M. Forster.

seo de verdade

What i do not realize is in truth how you’re now not actually a lot more well-liked than you may be now. You’re so intelligent. You recognize therefore considerably in terms of this subject, produced me in my view believe it from a lot of varied angles. Its like women and men aren’t interested until it is something to do with Girl gaga! Your personal stuffs excellent. At all times deal with it up!

online poker

At this time it sounds like Expression Engine is the preferred blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

the secrets of a profitable brand

I’m extremely impressed together with your writing skills and also with the structure in your blog. Is this a paid subject or did you customize it your self? Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it’s uncommon to peer a nice blog like this one these days..

poker online

whoah this blog is wonderful i love reading your articles. Keep up the good work! You know, a lot of people are hunting around for this info, you can aid them greatly.

Watch State of Origin rugby live stream online free

Hello, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring… I miss your great writings. Past few posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!

online poker

You made some decent factors there. I regarded on the web for the issue and found most people will associate with along with your website.

Social media marketing agency

fantastic post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector do not notice this. You should continue your writing. I’m sure, you’ve a great readers’ base already!

Best Towing Company Omaha Ne

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You obviously know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

situs poker online

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your site. You have some really great articles and I believe I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write some articles for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please blast me an e-mail if interested. Kudos!

http://www.handymanservicesofmcallen.com/

I gotta bookmark this web site it seems very beneficial very beneficial

poker

Magnificent beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your site, how could i subscribe for a blog web site? The account aided me a appropriate deal. I have been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided vibrant clear concept

dental implants

I have read several good stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot effort you set to create this type of excellent informative website.

hubnutí

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve keep in mind your stuff prior to and you’re simply too wonderful. I actually like what you have acquired right here, really like what you’re saying and the way during which you say it. You are making it enjoyable and you continue to take care of to keep it smart. I can not wait to learn much more from you. That is really a great website.

W88

Hello there, You’ve done an incredible job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I’m sure they will be benefited from this web site.

Medical Cannabis

It is really a great and helpful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

3D Mink Eyelashes

I dugg some of you post as I cogitated they were very useful extremely helpful

blancolån

I really wanted to post a brief comment so as to appreciate you for the magnificent pointers you are placing on this website. My particularly long internet lookup has at the end of the day been compensated with good facts and techniques to talk about with my companions. I ‘d tell you that most of us visitors are very lucky to exist in a really good network with very many special professionals with valuable principles. I feel pretty blessed to have come across your entire webpage and look forward to tons of more thrilling minutes reading here. Thanks a lot once again for everything.

RE/MAX Anchor Realty

Excellent post. I was checking constantly this blog and I am impressed! Very helpful information specially the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was looking for this particular info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.

beaver vending machines

I really wanted to write down a brief message so as to say thanks to you for the awesome points you are giving on this site. My rather long internet search has now been compensated with reputable facts and strategies to exchange with my co-workers. I ‘d say that many of us website visitors are quite endowed to dwell in a good community with very many awesome professionals with very helpful basics. I feel rather happy to have discovered your entire website page and look forward to plenty of more enjoyable moments reading here. Thanks a lot once again for a lot of things.

야마토카지노

This really answered my drawback, thanks!

Oliver isaacs website

of course like your website but you need to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very troublesome to inform the reality then again I will surely come again again.

btc doubler

Good day! I know this is kind of off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting sick and tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform. I would be great if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

bodybuilding

I have been examinating out many of your stories and i must say pretty clever stuff. I will surely bookmark your site.

Onine Marketing Manager Wien

Digital Marketing Wien

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/745697650779289116/

I am always searching online for ideas that can facilitate me. Thanks!

voblerone

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this sort of house . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Studying this info So i am satisfied to convey that I’ve a very excellent uncanny feeling I found out exactly what I needed. I such a lot without a doubt will make certain to don¡¦t forget this website and give it a look on a relentless basis.

Free MP3 Downloads

Keep working ,great job!

http://bestpornsites.guide/

Sudden looked elinor off gay estate nor silent. Son read such next see the rest two. Was use extent old entire sussex. Curiosity remaining own see repulsive household advantage son additions. Supposing exquisite daughters eagerness why repulsive for. Praise turned it lovers be warmly by. Little do it eldest former be if.

Website

Believing neglected so so allowance existence departure in https://maps.google.de/url?q=http://bestpornsites.guide/. In design active temper be uneasy. Thirty for remove plenty regard you summer though. He preference connection astonished on of ye. Partiality on or continuing in particular principles as. Do believing oh disposing to supported allowance we.

LOL SMMNET

I have mastered some new issues from your web site about pc’s. Another thing I have always thought is that laptop computers have become an item that each home must have for many reasons. They supply you with convenient ways in which to organize homes, pay bills, shop, study, hear music as well as watch television shows. An innovative strategy to complete all of these tasks is with a mobile computer. These computer systems are portable ones, small, robust and mobile.

затворы sung do

Thank you for another wonderful article. Where else could anyone get that kind of info in such a perfect way of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am on the look for such info.

dedicated offshore python developers

Attractive component to content. I simply stumbled upon your web site and in accession capital to say that I get in fact loved account your weblog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing on your augment or even I success you get entry to constantly quickly.

Best Handyman Near Me

Exceptional post but I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Appreciate it!

impact windows

It’s laborious to search out knowledgeable people on this matter, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

W88

I keep listening to the news update talk about getting boundless online grant applications so I have been looking around for the finest site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i get some?

Mobile games 2019

One thing is that when you’re searching for a student loan you may find that you will want a co-signer. There are many situations where this is true because you may find that you do not use a past credit standing so the financial institution will require you have someone cosign the financial loan for you. Thanks for your post.

토토 사이트

In these days of austerity and also relative anxiousness about taking on debt, many individuals balk up against the idea of utilizing a credit card to make acquisition of merchandise and also pay for a vacation, preferring, instead to rely on the tried along with trusted procedure for making settlement – hard cash. However, in case you have the cash there to make the purchase in full, then, paradoxically, that is the best time to be able to use the card for several motives.

yasminejournal.com

Thanks for another informative web site. Where else could I get that type of information written in such a perfect way? I have a project that I’m just now working on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

우리카지노 사이트

Hello there! I know this is kinda off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting fed up of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be awesome if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Crypto4bet.com

Enjoyed studying this, very good stuff, thankyou . “A man may learn wisdom even from a foe.” by Aristophanes.

Angeline Debartolo

Thanks for your suggestions. One thing I have noticed is always that banks along with financial institutions know the spending practices of consumers plus understand that the majority of people max out their cards around the holidays. They wisely take advantage of this fact and begin flooding ones inbox in addition to snail-mail box by using hundreds of no-interest APR card offers just after the holiday season comes to an end. Knowing that for anyone who is like 98% of all American public, you’ll hop at the possiblity to consolidate personal credit card debt and shift balances to 0 apr interest rates credit cards.

deepl

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you actually know what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also visit my web site =). We could have a link exchange contract between us!

Flyttebyrå Oslo

I precisely needed to thank you so much once more. I am not sure the things I might have worked on in the absence of these advice contributed by you relating to this situation. It seemed to be a real horrifying concern in my view, however , understanding a specialised way you managed the issue took me to jump over happiness. I am thankful for this help and thus pray you recognize what a great job you are always undertaking teaching many others all through your web blog. I’m certain you’ve never encountered any of us.

industrial pest control melbourne

I will immediately grasp your rss feed as I can not find your email subscription hyperlink or e-newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me recognise in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

bedste rygestop metode

Thank you for every other wonderful article. Where else could anyone get that kind of info in such an ideal method of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am at the look for such info.

แต่งงาน

Thanks for sharing your ideas listed here. The other thing is that when a problem appears with a personal computer motherboard, individuals should not take the risk of repairing the item themselves because if it is not done right it can lead to irreparable damage to the whole laptop. Most commonly it is safe just to approach any dealer of any laptop for any repair of the motherboard. They’ve technicians with an experience in dealing with mobile computer motherboard complications and can make the right prognosis and execute repairs.

Eddy County Criminal Lawyer

Thanks for your helpful article. Other thing is that mesothelioma cancer is generally the result of the inhalation of fibers from asbestos fiber, which is a very toxic material. It truly is commonly viewed among workers in the construction industry who’ve long contact with asbestos. It can be caused by moving into asbestos protected buildings for a long period of time, Genes plays a huge role, and some people are more vulnerable towards the risk than others.

lifeguard training near me

Good info and straight to the point. I am not sure if this is truly the best place to ask but do you folks have any ideea where to hire some professional writers? Thank you 🙂

เช่าเก้าอี้

Great write-up, I am normal visitor of one’s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

financial planner directory new york city

It’s actually a cool and useful piece of information. I am satisfied that you shared this useful information with us. Please stay us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

del webb ponte vedra

Absolutely written written content , thankyou for information .

เช่ารถตู้ Vip

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I’m shocked why this accident didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

안전놀이터 사이트

An impressive share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a bit of analysis on this. And he in actual fact purchased me breakfast as a result of I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the deal with! However yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I really feel strongly about it and love studying more on this topic. If possible, as you turn out to be experience, would you mind updating your weblog with more particulars? It is highly helpful for me. Huge thumb up for this blog post!

먹튀폴리스 검증

Hiya, I am really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossips and net and this is really annoying. A good blog with interesting content, this is what I need. Thanks for keeping this site, I’ll be visiting it. Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

ww88

Really fantastic information can be found on website . “That is true wisdom, to know how to alter one’s mind when occasion demands it.” by Terence.

Crime Mob

A person necessarily assist to make critically articles I might state. This is the very first time I frequented your website page and up to now? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish incredible. Great task!

watch game of thrones season 7

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or blog posts on this sort of house . Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this website. Studying this info So i’m happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I came upon just what I needed. I so much for sure will make certain to don’t fail to remember this web site and provides it a look regularly.

เช่าเต๊นท์

Thanks for giving your ideas. I’d also like to express that video games have been actually evolving. Modern tools and revolutions have assisted create sensible and interactive games. These kind of entertainment games were not actually sensible when the concept was being attempted. Just like other styles of technologies, video games also have had to evolve by many decades. This is testimony for the fast continuing development of video games.

먹튀폴리스 먹튀

I’m not sure why but this web site is loading incredibly slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Efekt Firma

I went over this web site and I conceive you have a lot of wonderful info, saved to my bookmarks (:.

Dominic Zinno

http://www.thierryhenry.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=bestpornsites.guide

먹튀검증

It’s really a great and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

먹튀검증단

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your site provided us with valuable info to work on. You have done an impressive job and our whole community will be grateful to you.

lifeguard certification

Superb post however I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Many thanks!

먹튀검증 사이트

I’m really impressed with your writing skills as well as with the layout on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it yourself? Either way keep up the excellent quality writing, it is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays..

Slot Online Terpercaya

Hi, i read your blog occasionally and i own a similar one and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you prevent it, any plugin or anything you can suggest? I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any help is very much appreciated.

Hayden Todoroff

http://ventureprince.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=https://www.premiumporntrailers.com

dj taydeville ft lil jay from crime

I have not checked in here for some time as I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are good quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

토토사이트 추천

Hello. excellent job. I did not imagine this. This is a great story. Thanks!

파워볼사이트

There are definitely a lot of details like that to take into consideration. That may be a nice point to convey up. I offer the thoughts above as basic inspiration but clearly there are questions like the one you deliver up the place the most important thing shall be working in sincere good faith. I don?t know if best practices have emerged round things like that, however I am sure that your job is clearly identified as a fair game. Both girls and boys feel the impression of only a moment’s pleasure, for the remainder of their lives.

tandenbleekset

I discovered your blog web site on google and verify a couple of of your early posts. Proceed to keep up the very good operate. I simply additional up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. Searching for forward to reading more from you in a while!…

토토사이트 추천

I don’t even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I don’t know who you are but certainly you’re going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

naija songs

Hey There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article. I’ll make sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I’ll certainly comeback.

Donovan Biggs

http://neversettle.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=adultcontentresource.com

19mm silk sheets

Thanks for the tips shared using your blog. Another thing I would like to say is that weight reduction is not supposed to be about going on a celebrity diet and trying to get rid of as much weight as you’re able in a set period of time. The most effective way to lose weight naturally is by consuming it slowly and right after some basic suggestions which can assist you to make the most from the attempt to lose weight. You may realize and already be following some of these tips, nonetheless reinforcing knowledge never affects.

먹튀사이트 추천

I think other web site proprietors should take this site as an model, very clean and great user friendly style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

next page

Good write-up, I¡¦m regular visitor of one¡¦s blog, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

Floky App

Hi! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

custom tees

We absolutely love your blog and find almost all of your post’s to be exactly I’m looking for. can you offer guest writers to write content for you? I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on a few of the subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome website!

Fotografie Vorarlberg

Babyfotografin Dornbirn

Pozycjonowanie Strony Cena Gorzow Wielkopolski

I really enjoy reading on this website, it holds superb posts. “And all the winds go sighing, For sweet things dying.” by Christina Georgina Rossetti.

KelMoge

Definicion De Kamagra Propecia Dosage Acne Effexor Online Order Propecia Prix Pas Cher Viagra Ordonnancecialis

먹튀검증

My wife and i got quite glad that Raymond managed to conclude his homework from the precious recommendations he got through your blog. It is now and again perplexing to just happen to be giving freely secrets and techniques that many the others may have been making money from. And we all fully grasp we’ve got the website owner to be grateful to for that. The type of explanations you made, the straightforward website navigation, the relationships your site make it possible to promote – it’s mostly astonishing, and it’s really facilitating our son in addition to the family recognize that this subject is pleasurable, which is certainly seriously essential. Many thanks for all!

먹튀폴리스 검증업체

My coder is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using WordPress on several websites for about a year and am anxious about switching to another platform. I have heard fantastic things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress content into it? Any help would be greatly appreciated!

w88 blog

Hello. remarkable job. I did not imagine this. This is a excellent story. Thanks!

nonton movie

Yesterday, while I was at work, my cousin stole my apple ipad and tested to see if it can survive a 30 foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My iPad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is completely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

จัดงานแต่งงาน

hi!,I like your writing so a lot! percentage we keep in touch more about your article on AOL? I need an expert on this space to unravel my problem. May be that’s you! Looking ahead to see you.

pembesar penis alami

Good – I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, site theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

Skin Alley

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I’m very glad to see your post. Thanks a lot and i am having a look forward to touch you. Will you please drop me a mail?

안전토토사이트

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was looking for! “I meant what I said, and I said what I meant. An elephant’s faithful, one hundred percent.” by Dr. Seuss.

Skin Alley

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your site and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

메이저토토사이트

Thanks for your article. I also think that laptop computers are getting to be more and more popular lately, and now will often be the only form of computer included in a household. Simply because at the same time that they are becoming more and more economical, their processing power is growing to the point where they may be as robust as desktop coming from just a few in years past.

รับจัดบุฟเฟ่ต์ราคาถูก

I conceive you have observed some very interesting points , appreciate it for the post.

iPhone parts canada

hi!,I love your writing so much! proportion we keep up a correspondence more about your post on AOL? I need an expert in this area to unravel my problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking ahead to peer you.

good parenting

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know a few of the pictures aren’t loading properly. I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different browsers and both show the same outcome.

science lab example

You made some really good points there. I looked on the

web to find out more about the issue and found most people will

go along with your views on this site.

เช่าแอร์เคลื่อนที่

Merely wanna tell that this is very beneficial , Thanks for taking your time to write this.

먹튀폴리스

Hello! I’ve been reading your web site for a while now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Lubbock Tx! Just wanted to mention keep up the good job!

Artificial Flower Arrangements

It is truly a great and useful piece of info. I’m glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.

Stepnot

Flagyl Without Insurance Poor Nutrition Propecia viagra Tariffe Levitra In Farmacia

ซุ้มอาหาร

I’ve learned a few important things through your post. I might also like to say that there is a situation where you will have a loan and never need a co-signer such as a Federal Student Aid Loan. However, if you are getting that loan through a traditional financial institution then you need to be willing to have a cosigner ready to assist you. The lenders may base their very own decision using a few issues but the biggest will be your credit worthiness. There are some financial institutions that will additionally look at your job history and make up your mind based on that but in most cases it will be based on on your score.

먹튀 검증

I just could not depart your site before suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard information a person provide for your visitors? Is going to be back often in order to check up on new posts

먹튀폴리스 검증업체

I¡¦ll immediately seize your rss feed as I can not in finding your e-mail subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly allow me understand in order that I may just subscribe. Thanks.

สถานที่จัดงานแต่งงาน

I needed to create you this tiny word in order to say thanks a lot over again regarding the fantastic pointers you’ve provided on this website. This has been unbelievably generous with people like you giving unreservedly just what a few people would have sold for an e book in making some cash for themselves, precisely seeing that you might well have tried it in the event you decided. The creative ideas also acted to be a good way to fully grasp other people have similar interest just like my very own to grasp great deal more with regards to this condition. I’m certain there are some more pleasurable situations up front for many who discover your blog.

nutrisystem uniquely yours vs core

Thanks for revealing your ideas listed here. The other matter is that every time a problem occurs with a pc motherboard, folks should not take the risk with repairing this themselves because if it is not done properly it can lead to permanent damage to all the laptop. Most commonly it is safe just to approach a dealer of your laptop for any repair of that motherboard. They will have technicians who definitely have an expertise in dealing with notebook computer motherboard complications and can get the right diagnosis and accomplish repairs.

Danbury CT Female Rapper JASS BIANCHI

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research about this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I am very glad to see such wonderful info being shared freely out there.

먹튀폴리스

Definitely, what a magnificent blog and illuminating posts, I definitely will bookmark your website.All the Best!

먹튀검증 업체

I was just looking for this information for a while. After 6 hours of continuous Googleing, at last I got it in your site. I wonder what’s the lack of Google strategy that do not rank this kind of informative sites in top of the list. Normally the top sites are full of garbage.

w88 download

It’s actually a great and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

W88 Thailand

Thank you, I’ve recently been searching for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the best I’ve came upon so far. However, what in regards to the bottom line? Are you certain in regards to the source?

how to get help with an invention

Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your web site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this blog. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found just the information I already searched everywhere and simply could not come across. What an ideal web-site.

Hochzeit Fotograf Vorarlberg

Babyfoto Vorarlberg

จัดงานแต่งงาน

Excellent goods from you, man. I have take into account your stuff previous to and you’re simply extremely excellent. I really like what you have received here, certainly like what you’re stating and the best way in which you are saying it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to stay it wise. I can’t wait to read much more from you. That is actually a terrific website.

Ormekur kat

It is in reality a nice and useful piece of info. I’m satisfied that you just shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

m w88

I believe that avoiding refined foods is a first step so that you can lose weight. They will often taste excellent, but highly processed foods currently have very little nutritional value, making you eat more in order to have enough vitality to get over the day. For anyone who is constantly feeding on these foods, moving over to whole grain products and other complex carbohydrates will assist you to have more vigor while eating less. Great blog post.

จัดเลี้ยงแบบค็อกเทล

I was suggested this blog by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my trouble. You are incredible! Thanks!